There’s been a renewed interest in the site of the former United States Steel South Works following Dave Matthews Band Caravan‘s use of the area. Thinking readers might enjoy a little history of the site, I’ve edited a few excerpts from my master’s thesis on the development (and decline) of the site and posted them here along with some supporting materials.

Compiled and aligned maps from USGS, Department of War, USS and other sources

In the mid-1800s, Chicago’s iron foundries were located on the north side of the Chicago River, but as the city expanded and demand for metal products boomed, iron and steelmakers sought space to spread out. While some business moved north, many eventually made their way to the Calumet area, which was not incorporated as a part of southeastern Chicago until the late 1880s. Businesses moved south in part due to the efforts of the Calumet Canal and Dock Company, which promoted the region as near industrial paradise. Claimed benefits of the region included lower taxes, access to rail and water traffic, and recent improvements by the Army Corps of Engineers. Among those companies lured were Pullman, which created the town of Pullman in 1881, and the North Chicago Rolling Mill Company, which bought the future site of the South Works in 1880.

The North Chicago Rolling Mill Company was founded in 1857 by Captain E.B. Ward to satisfy demand for railroad rails that was fueled by western expansion and a general boom in railroad construction. The company came to prominence in 1865 as the first company to roll steel rails rather than the much less durable iron rails. Despite a number of improvements to the North Works, Orrin W. Potter, President of the Rolling Mill Company, and other business partners realized that the North Works was too cramped to meet ballooning demand for steel rails. As such, they needed to create another works, so on March 28, 1880, the Rolling Mill Company bought 73 acres of land with 1,500 feet of frontage on the Calumet River and 2,500 feet on Lake Michigan and broke ground for what would become the first integrated rail mill in the world.

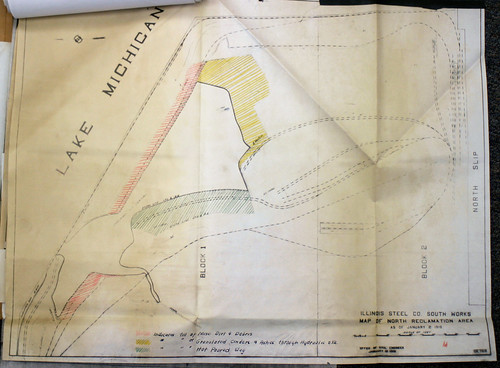

After acquisition of the marsh and beach land, the Rolling Mill Company began adding to the littoral transport of sediment that was trapped by the new government “improvements” with “great quantities of slag and refuse from their mills, on the shore and in the lake along it thereby artificially increasing the natural advance of the shore line.” By 1882, more than 30 acres of land had been added to the site.

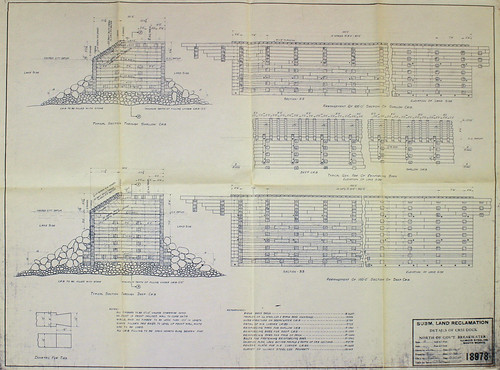

This was the beginning of a long phase of expansions of the site that was conducted by a variety of owners, including United States Steel, until the late 1920s. Over the years, hot slag, granulated cinders and dirt were slowly poured into the site using small railroad cars. The location of the types of deposits is only partially known. Records of the deposits were regularly collected and noted by the site owners, but (at least surviving) maps were not cumulative for the process, so only spotty records of the types and times of fill exist.

An Illinois Steel Company map showing infill on the north end of the “reclamation” area, 1919

Detail of a crib wall used during the infill process, 1914

By 1933, USS had completed infill activities and had nearly saturated the now 576 acre site with buildings without establishing a coherent plan for expansion. While the South Works would operate for another sixty years, this design problem would be a major factor in its undoing. While an attempt to “reclaim” an additional 194 acres from Lake Michigan was floated in 1963, the expansion was never made, and investments became increasingly sporadic as the global steel trade underwent extreme changes.

By the early 1980s, plant closure was certain after a major planned expansion was cancelled. Within 22 years starting in 1970, the Works changed from a major steel operation with a rated annual steel capacity of over seven million tons and more than 10,000 employees to a plant with a capacity of only 44,000 tons and 690 employees at its closing in April 1992. Massive demolitions were well underway.

USGS aerial photographs of the South Works from 1983 and 1994 showing massive demolition of site structures

After closure, the site continued to be fiscally productive for the company through slip leasing, utility negotiations and other activities, but it slowly gained its derelict appearance despite EPA activities, the proposed Solo Cup plant and the park service expansion along the coast.

Looking into the north ore bins, 2003

Today, the most prominent structures are the ore bin walls, which have massive holes in them from the crane removal process. Wildlife has thrived in the interiors of these ore bins, with the concrete pad providing easy development of a wetlands and many of the supporting flora and fauna. When walking the site in 2003 and 2004, I saw or saw evidence of animals as diverse as horned owls, deer and foxes.

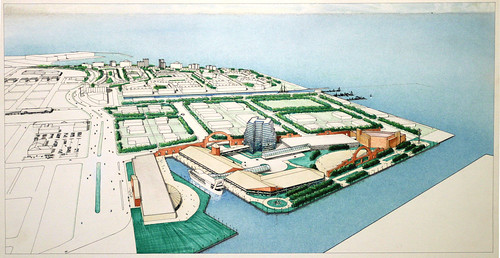

USS has experimented various plans for the site over the last twenty years with little luck, although it looks like the USS/McCaffery Interests current development plan may be realized in some capacity. Whether the development looks anything like the current proposal is anybody’s guess.

A previous development plan

The current promotional video for redevelopment

- Let me know if you’d like a citation for any of this material. The records of USS, the EPA and a variety of local historical societies were helpful in defining the history outlined above. Additionally, Kenneth Warren’s Big Steel: The First Century of the United States Steel Corporation, 1901-2001 and trade publications from the day were invaluable.